The period of nightmare

is over’

Looks like it’s Sardar season

Calcutta, Dec.05, 2004

The Telegraph

Looks like it’s Sardar season. In the handling of the nation and its economy — and now with the appointment of its army chief — the Sikh community is enjoying its place in the sun. Avijit Ghosh reports

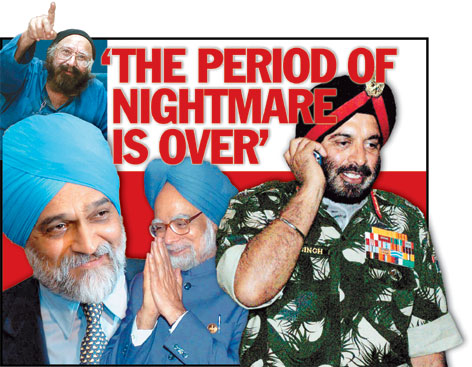

At the top: (Clockwise from top left) Khushwant Singh (pic: Rajesh Kumar);

J.J. Singh; Manmohan Singh; Montek Singh Ahluwalia

Bitter memories are like festering sores. But sometimes, the slate is wiped clean: the old order is altered, the forbidden becomes the preferred and hope comes calling in renewed vigour.

Last week, when Lt Gen. Joginder Jaswant Singh was named the new army chief, the first Sikh to hold the position in India’s 57 years of Independence, the effect on the community was similar. Many Sikhs nursed an emotional grievance that the turban was discriminated against when it came to the army’s top job.

But the new turn of events has changed all that. As senior Akali leader Kanwaljit Singh puts it, “The development carries the message that the suspicion on the loyalty of the Sikh community towards the nation since 1984 has finally been demolished.”

This is the Sardar’s season. Be it governing the nation, handling its economy or protecting its frontiers — the community is enjoying its finest moment in two decades. So what if he has no political base, Prime Minister Manmohan Singh is a Sikh. So is Montek Singh Ahluwalia, the deputy chairman of the Planning Commission. And when J.J. Singh becomes India’s army chief early next year, the triangle will be complete. Sitting on his favourite chair in his Sujan Singh Park residence, writer Khushwant Singh smiles and says, “It’s a sea change. I think the period of nightmare is over.”

Twenty years ago, the Sikhs were an alienated people. Punjab was ravaged by militant killings and army bullets. But as the army’s attempt to rid the Golden Temple of militants led to the killing of thousands, extremism gathered deeper roots. On October 31, 1984, when Indira Gandhi was assassinated by her Sikh bodyguards, thousands of Sikhs were massacred. Says the 90-year-old writer, “It was not spontaneous but organised. It took place only in the Congress-governed states. Then the sense of alienation became acute.”

Slowly over the years, peace has returned to Punjab. And the 20-million-strong community spread in all corners of India is now making a return journey to the mainstream. The signs are there for everyone to see. Hindi cinema, that unfailing barometer of the popular pulse, shows a distinct approval of the Sikh ways. Who would have imagined a passionate Sardar lover — beard, turban and all — in a Hindi film? But Sunny Deol — in the superhit Gadar of 2001 — caught the change in the air.

Over 10 per cent of the dialogues in this year’s biggest Bollywood hit, Veer Zaara, is in Punjabi with Amitabh Bachchan playing a Sikh character. And, though Daler Mehndi doesn’t sell a million albums anymore, Bhangra pop continues to thrive. Rabbi is the new bearded hot thing in Sufi-pop. “The turban,” says satirist Jaspal Bhatti, “has gained both acceptance and approval like never before.”

The transition was tough. The feeling of alienation had only increased in the post-1984 years. Many poor and helpless Sikhs were often picked up by the lawmen for questioning. “Whenever there was a Delhi blast, the police used to harass us. The logic seemed to be: since these guys survived the riots, they must be working on revenge,” says riot victim Surjit Singh.

Even in 1987, a Sikh was often looked at with suspicion. Playwright Gursharan Singh recalls fellow passengers discussing his bag during a train journey from Delhi to Lucknow. “Is he carrying bombs, they were wondering aloud,” he recalls.

A community’s return to the mainstream — the ebbing away of alienation — is not so much an event as a process. But lawyer H.S. Phoolka, who is still fighting the cases of 1984 riot victims, believes that the tide started turning in the early Nineties. “For the first time, during V.P. Singh’s tenure as Prime Minister, the government admitted to wrongs which needed to be rectified. Even during Chandrashekhar’s brief regime some cases were reopened,” he says. These were the first hesitant beginnings in a long quest for justice which continues even today.

But Kanwaljit, who has also served as Punjab’s finance minister, believes that the change came about with the emergence of coalition politics and by reverting the focus of policy-making to the region; thereby giving it its due importance.

A minority community often looks out for signals and messages which underscore a government’s intent towards it and which make or break its collective perceptions. To a greater or lesser degree, depending on their own personal experiences, most Sikhs are thrilled with the recent developments.

And the feeling holds good even for the NRI Sikh, many of whom migrated during the peak of Punjab militancy and who continue to be vocal critics of the Indian state. During a visit to the US last July after Manmohan Singh became Prime Minister, Gursharan Singh was surprised at the change of tenor in most Sikh newspapers published there.

“Their usual tone is that the Sikhs are having a bad time in India. There was a change in that trend this time. Now with J.J. Singh all set to be the army chief, it is likely to get more positive,” he says.

But Patwant Singh, author of the seminal work, The Sikhs, believes that wounds cannot heal until the guilty are punished. He has a direct query: “Why has nobody been convicted so far?”

It is a question many riot victims are asking as well. For men like Surjit Singh, who lost 13 family members, forgetting is impossible. For him, as for those who have been through the worst of the killings, little has changed.

Yet, undeniably, for most Sikhs the past few months have rung in hope and promise. Having the Prime Minister and the Chief of Army Staff from their own community has filled them with a sense of community pride and given them the feeling of being an integral part of the Indian mainstream. As literateur Ajeet Cour says, “History is full of such wounds. Life demands that one reconciles. It is important to forgive, even if one cannot forget. And move on.”

And those left out...

Bereft: Women who lost their families in the 1984 anti-Sikh riots; lawyer H.S. Phoolka; Photos: Prem Singh

The boys of Garhi, a resettlement colony for the 1984 riot victims in south Delhi, call themselves free. Free is their word for being unemployed. Those who were barely four years old or less — a couple even in their mother’s womb — when their grandfathers, fathers and uncles were slaughtered have grown up to be tall, gawky men.Most of them dropped out of school early and grew up playing in the bylanes of these humblest of DDA flats their mothers received after spending months in the relief camps. But you can’t blame the mothers for their lack of education. Before their lives changed so dramatically following the anti-Sikh riots, they were homemakers for mechanical engineers, ex-armymen and shopkeepers.

Suddenly, with every grown-up man in the family dead, they had to go out on work even though the job wasn’t much to be pleased about. They worked, and still do, as errand women, dais, gardeners and cleaners. Any job that keeps the home fires burning. At daytime on weekdays, you will not find any middle-aged woman in the colony.

Young Jagjit Singh knows how he grew up. “I grew up standing in the queue for water,” he says. The C-block, where these victims live, has an acute water problem. Pots and pails lie in dozens outside every flat; everyone queues up when the water-tanker comes. Like him, his 24-year-old friend, Gurpreet — with a Salman Tere Naam Khan hairstyle — never finished school. A few months ago, he bought a second-hand Maruti van on loan. But the boys from the bordering mohalla keep breaking its glass. He doesn’t know much about J.J. Singh, all set to become the first Sikh army chief. But he knows that when there is a fight, sometimes those boys taunt him with the question, Bhool gaye kya?

The widows of Garhi are not eagerly waiting for justice, though each one will welcome it with open arms. They just want to get out of this endless cycle of misery that circumstance has thrust on them. “We lost our men,” says Bakshish Kaur, “but today the government should be thinking about our kids”.

One of the boys points out the irony of their existence. “Sometimes they make fun of us and say, you have a Prime Minister but you still have to stand in queue for water,” he